We often discuss various stainless steel processing techniques such as castability, forgeability, machinability, weldability, and heat treatment, but do we truly understand these terms completely? Many might have a general idea of what these processes entail, but explaining them in detail can be challenging. Below is a compiled introduction to common stainless steel processing techniques for reference.

Stainless steel is widely used due to its excellent corrosion resistance. Currently, there are many grades of stainless steel with varying formability, strength, and workability. Among them, 304 and 316 stainless steels are two of the most commonly used types.

304 Stainless Steel (also known as A2 stainless steel) contains 18–20% chromium and 8–10% nickel. 316 Stainless Steel(also known as A4 stainless steel) contains approximately 16% chromium, 10% nickel, and 2–3% molybdenum. The key difference between 304 and 316 stainless steels is the presence of molybdenum in 316, which is absent in 304.

The addition of molybdenum enhances resistance to chloride corrosion. Furthermore, 316 stainless steel contains trace amounts of silicon, carbon, and manganese, making it more resistant to chemical corrosion, such as fatty acids and sulfuric acid at high temperatures. Additionally, 316 stainless steel can withstand temperatures up to 871°C, while 304 has slightly lower heat resistance. Hence, 316 stainless steel is commonly used in marine applications.

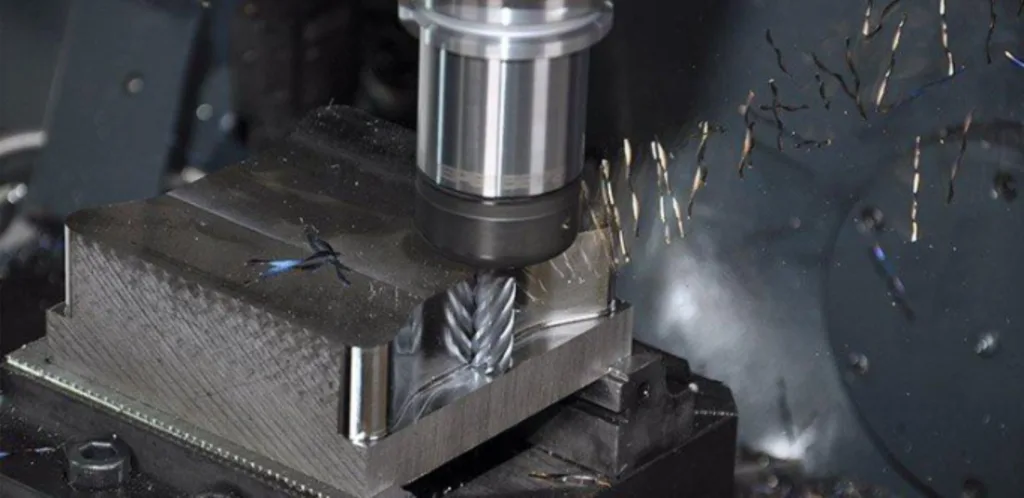

Machinability

304 stainless steel is easier to machine compared to 316. It is also easier to clean, making it ideal for decorative finishes. 316 stainless steel is harder to machine and requires specialized tools for cutting. Therefore, 316 is only used when other stainless steels cannot meet the application requirements.

Processing Methods

Both 304 and 316 stainless steels require heavy-duty machinery due to significant vibrations during processing. Tools made of carbide or high-speed steel (HSS) are recommended. HSS tools perform better at lower cutting speeds. All 300-series stainless steels exhibit some degree of work hardening, with 316 being more prone to hardening. Measures such as using sharp tools, lower speeds, and higher feed rates can mitigate this. For complex 304 parts, deep cuts with high feed rates minimize work hardening.

Castability of Stainless Steel

Castability refers to the ability of stainless steel to produce qualified castings through casting. It includes fluidity, shrinkage, and segregation. Fluidity is the molten metal’s ability to fill a mold; shrinkage refers to volume reduction during solidification; segregation describes chemical and structural inhomogeneity caused by uneven cooling.

Tips for Machining Stainless Steel

1. For cutting rods under φ40 mm, use HSS cutoff tools for optimal results. For larger diameters (φ40+ mm), carbide tools improve efficiency due to lower cutting speeds.

2. Set the tool’s rake angle to 0° (grind on a tool grinder if possible). This prevents chip clogging and tool breakage caused by friction.

3. Avoid excessive tool tip radius, as it accelerates flank wear due to thinning chips and work hardening.

4. Sharpen tools promptly. Monitor both primary and secondary flank wear—excessive secondary wear narrows grooves, hindering chip removal.

5. Ensure a smooth tool surface to reduce adhesive wear and cutting forces. Grinding a 0.2 mm negative chamfer on the edge minimizes chipping. Use YG8 carbide for better rigidity and reduced adhesion.

6. Maintain a cutting speed of ~60 m/min. For rods φ40–φ80 mm, complete the cut in one pass without lateral movement. Break long chips to avoid hazards and minimize work hardening. When cutting solid workpieces, leave 1–2 mm at the center to snap manually.

Forgeability of Stainless Steel

Forgeability refers to the ability of stainless steel to undergo shape changes (e.g., forging, rolling, stretching, extrusion) without cracking, either hot or cold. This property is influenced by the material’s chemical composition.

Weldability of Stainless Steel

Weldability denotes the adaptability of stainless steel to welding processes. It involves two aspects:

1. Joint Integrity: Susceptibility to defects under specific welding conditions.

2. Service Performance: Suitability of the welded joint for intended use.

Heat Treatment of Stainless Steel

Common heat treatment processes include annealing, normalizing, quenching, tempering, solution treatment, precipitation hardening, and aging.

Annealing: Heating to a specific temperature, holding, and slow cooling to reduce hardness, enhance plasticity, relieve stress, and homogenize microstructure. Types include recrystallization, stress relief, spheroidizing, and full annealing.

Normalizing: Heating 30–50°C above Ac3/Acm, holding, and air cooling to improve mechanical properties, refine grains, or prepare for subsequent treatments.

Quenching: Heating above Ac3/Ac1, holding, and rapid cooling (e.g., in salt baths) to form martensite, enhancing hardness, strength, and wear resistance.

Tempering: Reheating quenched steel below Ac1 to relieve stress and balance hardness with toughness. Types include low-, medium-, high-temperature, and multiple tempering.

Solution Treatment: Heating to dissolve excess phases, followed by rapid cooling to create a supersaturated solid solution.

Precipitation Hardening: Strengthening via solute clustering or particle dispersion (e.g., aging at 400–800°C for austenitic steels).

Aging: Natural or artificial aging to stabilize dimensions and properties by relieving internal stress.

Hardenability

Hardenability refers to the depth and uniformity of hardness achieved during quenching. It depends on alloying elements, grain size, heating temperature, and cooling rate. High hardenability ensures consistent mechanical properties and reduces distortion.